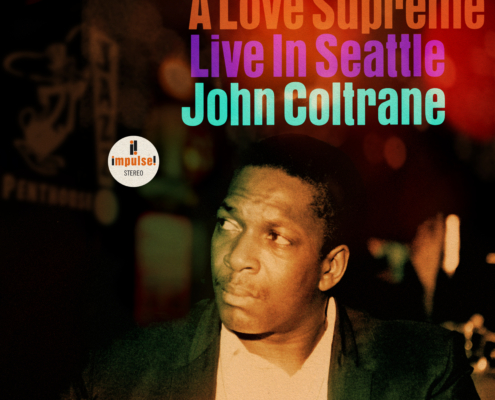

JOHN COLTRANE – A LOVE SUPREME: LIVE IN SEATTLE

John Coltrane gilt genreübergreifend als einer der wichtigsten Musiker aller Zeiten und einer der wahren musikalischen Innovatoren des letzten Jahrhunderts.

„A Love Supreme“ ist die berühmteste Musiksuite in der Geschichte des Jazz. Jahrelang dachte man, dass Coltrane das Programm seines ikonischen Studioalbums von 1965 nur einmal live beim Antibes Jazz Festival aufgeführt hatte … bis jetzt.

Ende letzten Jahres entdeckte das Team von Impulse! Records die Live-Aufnahme einer bisher unbekannten Aufführung der „Love Supreme“-Suite, ein Fund von historischer Bedeutung!

Aufgenommen am 2. Oktober 1965 im „Penthouse Club“ in Seattle, von einem Freund Coltranes, dem bekannten Seattle-stämmigen Musiker Joe Brazil, mit dem hauseigenen Aufnahmegerät des Clubs, versetzt diese Aufnahme den Hörer zurück an einen Ort, an dem Musikgeschichte geschrieben wurde. Joe Brazil war eine wichtige Figur in Coltranes Leben, der nicht nur in seiner Band auf dem „Om“-Album mitspielte, sondern auch Coltrane seiner zukünftigen Frau Alice vorstellte.

Diese Veröffentlichung fängt einen bedeutenden Moment in Coltranes Biografie ein. Obwohl es sich nicht um eine Aufnahme in Studioqualität handelt, strahlen die Kraft und Seele der neu gegründeten Gruppe in jedem Augenblick durch.

Es existiert bereits eine posthume Coltrane-Aufnahme unter dem Titel „Live In Seattle“, die im Rahmen der Konzerte des Künstlers an diesem Ort aufgenommen wurde. Dass die Gigs der restlichen Woche, und damit die Interpretation von „A Love Supreme“, ebenfalls aufgezeichnet wurden, war bisher nicht bekannt.

Bei der Seattle-Version von „A Love Supreme“ handelt es sich um die vollständige Suite mit einer aufregenden, erweiterten Bandbesetzung von insgesamt sieben Musikern inkl. der Mitglieder seines Classic Quartet (McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones) sowie niemand Geringerem als Pharoah Sanders bei seinem ersten offiziellen Auftritt als Teil von Coltranes Band.

Mit dieser bislang unbekannten Interpretation von Coltranes Jahrhundertwerk lernt der Hörer eine abenteuerlichere, faszinierend anders klingende Performance kennen. Eine noch freiere, stärker improvisatorische Herangehensweise an die ikonischste Musiksuite des amerikanischen Jazzkataloges.

| TRACKLIST |

| 1. |

|

||

| 2. |

|

||

| 3. |

|

||

| 4. |

|

||

| 5. |

|

||

| 6. |

|

||

| 7. |

|

||

| 8. |

|

A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle

We’re all human beings. Our spirituality can express itself any way and anywhere. You can get religion in a bar or jazz club as much as you can in a church. A Love Supreme is always a spiritual experience, wherever you hear it.

—Elvin Jones, 2002

For nearly six decades, two reels of ¼” recording tape held the only evidence of a rare and largely unknown 1965 performance of A Love Supreme by John Coltrane. The reels sat in the personal tape collection of Seattle saxophonist and educator Joe Brazil, the man who had made the recording. Over the years, he played it for a few fortunate friends and students. Brazil passed away in 2008. The memory of Coltrane performing his four-part suite during an historic run in Seattle in 1965 remained with a few witnesses who had caught the set and knew of its significance even then. More recently, a few archival sleuths caught the scent of the recording.

After Coltrane first recorded A Love Supreme in the studio in December 1964, once with his famous Classic Quartet and once with a sextet, we know he seldom chose to perform it: once at a French jazz festival in the summer of ’65, which was recorded and later released, and a year later at a fundraiser in a Brooklyn church, which was not. This recording offers the first evidence of the master of spiritual expression performing his his signature work in the close confines of a jazz club.

Of his many musical creations, Coltrane looked upon A Love Supreme in a very special light. He had meticulously crafted the composition, writing liner notes explaining its form and as a listener’s guideline. He had added his own voice to the music, chanting in the opening part “Acknowledgment,” and composed a lyrical poem that he “read” through his saxophone on the final section “Psalm”—“a musical narration of the theme ‘A Love Supreme,’” was how he put it. He called A Love Supreme a “humble offering” to the Divine; no other composition or recording was similarly offered nor did he append his signature to any other work. A Love Supreme was as much an individual testament as it was a public statement—a sermon of universalist belief.

Coltrane was born to a line of preachers. The very few times he chose to perform A Love Supreme in its entirety—“Acknowledgement”, followed by “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm”—one can assume there was a good reason, or reasons: the situation and the venue and the vibe warranted it, and so did the company—onstage and in the audience. This was not just message music, it was community music.

Future bloodhounds are sure to unearth more recordings of Coltrane’s performances like this one, and perhaps yet another take of A Love Supreme will be discovered. For now, we know this for certain: on October 2, 1965, a Saturday, in Seattle, the necessary elements were in alignment: music, players, venue, a spirit of connection, a certain political charge. Coltrane chose to perform it, and significantly, the moment was recorded. This is the story of that moment and the circumstances that led to it.

For John Coltrane 1965 marked a career crest. He was a major jazz star with mainstream stature and penetration, riding a wave of popularity boosted by his 1961 radio hit “My Favorite Things”, and that had continued through a number of top-selling albums on the Impulse label—including collaborations with Duke Ellington and singer Johnny Hartman. A Love Supreme, recorded in December of ’64 and rush-released two months later, had garnered a Grammy nomination and helped earn him Downbeat magazine’s Jazzman of the Year award.

By circumstance rather than plan, Coltrane fit into the zeitgeist of ’65. To many African Americans, Coltrane’s music—especially the more unbridled, ecstatic tracks—echoed the growing rage of the political moment. To many musicians, his experimental edge pointed the way forward to the next bold breakthrough in jazz; soon terms like “Energy Music” and “Fire Music”, and the general appellation “The New Thing,” would describe those who followed in his wake. Coltrane was expanding his core fanbase beyond jazz, winning over a younger, multiracial generation undeterred by categorical divides, devouring his music with the same passion they held for Motown and the Beatles, for Bob Dylan and James Brown.

The cross-generational appeal and pied-piper effect was impossible to ignore. In mid-October 1964, journalist Leonard Feather spoke with Coltrane at Shelly’s Manne-Hole in Los Angeles. In his Jazz Beat column, he wrote, with a degree of derision, that the saxophonist’s “most devoted followers are young listeners, many of whom are musically illiterate.” Coltrane’s response ignored the swipe. “I never even thought whether or not they understand what I’m doing. The emotional reaction is all that matters; as long as there is some feeling of communication, it isn’t necessary that it be understood.”

Moving on, Feather reported Coltrane “modestly shrugged off” the suggestion that his stylistic approach was creating a “cult” of followers.

I don’t think people are necessarily copying me. In any art there may be certain things in the air at certain times. Another musician may come along with a concept independently, and a number of people reach the same end by making a similar discovery at the same time.

Modest indeed. When that discussion took place, Coltrane was close to completing his last full year touring with his so-called Classic Quartet: pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, drummer Elvin Jones. Together since ’61, they had forged a sound that could be dense and intense, as well as spiritual and reflective; road-honed flavors unique to that foursome. Any change to that formula—upending the lineup, replacing the repertoire, rethinking that sound—was bound to challenge and draw criticism. Through 1965, onstage and in the studio, that’s exactly what Coltrane would do.

Hints of what Coltrane was thinking—the stylistic breadcrumbs—are in his recordings. A Love Supreme served as the most obvious example of a shift to original music of a resoundingly spiritual priority. The following album The John Coltrane Quartet Plays…, recorded in February and May ’65, includes two recent film or show tunes (“Chim Chim Cher-ee” and “Feeling Good”) and the standard “Nature Boy” (with a second bassist added); those tunes stand as the last time Coltrane would record non-original material in the studio.

But Ascension—recorded that June—was the true line in the sand. The session assembled an avant-garde big band featuring musicians of diverse experience and disparate abilities, loosely following a musical form more suggested than defined. Coltrane supplemented his quartet with six horn players—trumpeters Freddie Hubbard, Dewey Johnson; alto saxists Marion Brown, John Tchicai; and tenors Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders—plus bassist Art Davis. The results both excited and daunted the musicians, and placed Coltrane in a traffic cop role when perhaps he had hoped for a level of unspoken communication between the musicians similar to that of his quartet. „He was just very quiet and concentrated,” recalled Tchicai, “very much occupied in his mind with what he wanted to do.“ He remembered Coltrane giving „small directions, he didn’t say a lot. He just said, ‘Okay, we have this little theme here, and then at a certain point you come together in the piece and play this theme, and then you take a solo, and then after you it’s Freddie Hubbard…that was the kind of cues he gave us.”

Ascension was Coltrane’s most radical leap on all levels: the recording that most predicted his approach to live concerts—including his performance of A Love Supreme in Seattle the following October. It also represented the beginning of the end of the Classic Quartet.

Seattle was one stop buried in a steady tour itinerary that befit his standing. It kicked off days after the Ascension session, and that lasted through the second half of ’65. July and August included festival gigs, domestic and overseas—including his impromptu performance of A Love Supreme in Antibes, France on July 26—after which Coltrane returned home for the birth of his second son Ravi on August 6. He then rejoined the quartet, driving the group in his Chrysler station wagon out to dates in Cincinnati, Chicago, Cleveland, Columbus, and Indianapolis.

Just before the quartet departed for the Midwest, news arrived of historic impact from Los Angeles: on August 11, a white police officer had stopped an African American driver, leading to an altercation which sparked a six-day rebellion in the primarily black neighborhood of Watts. The duration of the unrest and televised images of urban devastation made stark the depth of ethnic disparity of the country. It refocused the energies of all involved with the Civil Rights movement, and established a historical pattern of brutality, bloodshed, and protest that continues to repeat itself over and over. No African American was untouched. Coltrane called to check on the family of the recently deceased Eric Dolphy who lived in Los Angeles. He and the group would open at the It Club in downtown L.A. in only a few weeks.

San Francisco was Coltrane’s next stop in mid-September. During a two-week run at the Jazz Workshop, he finally set in motion his plan to expand his lineup and effectively shift the group sound; the Classic Quartet would never again be a quartet. It began with two musicians sitting in nightly. Coltrane had played with both in rehearsal and jam situations, and both had recently relocated to San Francisco: Chicago-born bassist Donald Rafael Garrett, whom Coltrane had met in Chicago during his earliest days in Miles Davis’s quintet; and Arkansas-born saxophonist Pharaoh Sanders, whose sound Coltrane first heard while he was scuffling in New York City. In a 1967 interview with Coda magazine, Sanders—who recently played on Ascension—reported that Coltrane “told me then that he was thinking of changing the group and changing the music, to get different sounds. He asked me to play with him.” As to his own musical identity at the time, Sanders added:

I stopped playing on changes a long time ago, long before I started playing with Coltrane. They limited me in expressing my feelings and rhythms. I don’t live in chord changes. They’re not expanded enough to hold everything that I live and that comes out in my music.

The arrival of the new additions was immediately apparent. The cohesion of the performances loosened, and the onstage interaction became less intuitive and more deliberate. The demand on all the players to focus on each other was intensified, to discover a part to play or lay out, and to help find a collective coherence. Often, when Coltrane and Sanders weren’t playing, each would pick up a percussion instrument—a gourd, cowbell, or clave sticks—and add rhythmic texture. As much as Coltrane’s vocabulary on saxophone had included a certain level of dissonance and rougher edge, Sanders’s leaned even more to the instrument’s harsher—and shrill—edge. The two bassists divided their common instrument between them, Garrison most often staying low, at times bowing or strumming, while Garrett leaned on the higher range. Intriguingly, Coltrane’s sets offered a mixed bag of original compositions—some so new as to lack a title—alongside older melodies with which he was associated: “Body and Soul”, “Afro Blue,” “Lush Life,” and the perennial favorite, “My Favorite Things.” Often, the familiar became unfamiliar, as the group’s playing disengaged from discernible melodies and harmonies.

Coltrane “sensed he was onto something,” biographer Lewis Porter explains. “He no longer wanted to swing, and from this point on Garrison never played a walking bass with him, but broke up the beat with short phrases and strumming. Jones slashed away at full force, and Tyner’s fine work receded more and more into the background.”

The public, as well as certain bandmembers, were unready for the change. “It was a totally different direction— the audiences at the Jazz Workshop were kind of stunned. Not a lot of people would stay for the second set because it was so intense,” remembers drummer Terry Clarke, who had recently moved from his native Vancouver to play with Bay area saxophonist John Handy. He was in attendance for a number of the sets that week in San Francisco, and was asked to sit in during the Sunday matinee, experiencing the music from within—if for only one number.

It was all so new to us. I thought Sanders had a lot of balls to get up there and play with Trane—obviously it was a friendship that was deeply rooted in another kind of reality. We knew A Love Supreme of course and the idea of knitting together a theme for an album with different movements and making it more orchestral, like he had done in a way with Africa/Brass. But A Love Supreme was still very much a studio animal. Hearing his music live, it became more communal music—it was more about the communal aspect of it. It was like a school to establish one’s own personality. This was also a time where Trane was letting almost everybody come up and play. Elvin and I had been introduced and he invited me to go up and sit in—I had just turned 21 and completely flummoxed. My girlfriend at the time shoved me up on the bandstand.

My heart’s racing and they start playing. The whole atmosphere was extremely open—the tune started off in a mode, 8-bar phrases, McCoy starts rumbling, and I wasn’t really into this music at that point but here I am sitting on the Elvin throne! I went along as best I could with that mood, creating sounds and rumblings and getting frustrated with playing that way so I started to play quarter notes on the cymbal, going into four. Trane was just to my right and in a millisecond he was exactly with me and we start playing time which they hadn’t done while I had been listening. I remember it felt like taking off in a 747 and for a few minutes, almost everybody went into it. Jimmy Garrison dug in while McCoy kind of avoided it. I think I might have been up there for maybe 10 minutes, then Pharoah came up to play and I knew he wasn’t going to play in time. They went into this free thing and another drummer came up and took over.

The San Francisco engagement ended that evening—September 26. Coltrane, intrigued by the new sound that was developing, asked the recruits to travel with the group. Garrett would stick with Coltrane for another two weeks through his West Coast run and perform on a few more recordings. Sanders would remain until Coltrane passed in July 1967. Next stop: Seattle.

Coltrane, by all indications, only visited Seattle twice in his lifetime — once as a member of Johnny Hodges’s band in 1954, and once leading his own group, when this particular performance of A Love Supreme took place. Seattle, to a certain extent, was off the beaten path. Hosting the World’s Fair in 1962 made it less so, but in 1965, snugly seated in the northwest corner of the continental U.S., a twelve-hour drive from San Francisco, it was still in the process of becoming a consistent stop for most modern jazz headliners.

In the ‘60s, Seattle could boast of a healthy, diverse jazz scene including a number of players leaning in a modern, and even avant-garde direction. A number of clubs catered to local talent—Pete’s Poop Deck, the more R&B flavored Dave’s Fifth Avenue, and a few other venues open to the edgier, discordant jazz then on the rise, like the Llahngaelhyn. The latter was a café hosting after-hours jam sessions that sometimes drew nationally known players who had performed elsewhere earlier in the evening: Roland Kirk, McCoy Tyner and Chick Corea. That “elsewhere” was The Penthouse that offered jazz headliners of the day. Charlie Puzzo, a bartender originally from Torrington, Connecticut who followed a group of hometown friends to Seattle after World War II, was the no-nonsense, street-wise proprietor. In 1961, a few months before Seattle would host the World’s Fair, he decided to lease the ground floor of the Kenneth Hotel in the city’s cultural hub of Pioneer Square. Puzzo’s inspiration was a chain of gentleman’s club then trending.

“Charlie was trying to ride the crest of popularity of Playboy magazine and clubs without any direct references,” says Jim Wilke, a member of the Seattle Jazz Society of that era. Wilke was also a deejay with KING, hosting weekly live broadcasts from The Penthouse on Thursdays.

The wait staff were attractive young women in leotards but no ears or bunny tail, and the poles on one side of the club were shaped like elongated rabbits. It was a typical Pioneer Square storefront—you entered from the street straight into the club, the bar was off to the left. It was long and narrow, I would say 25 feet wide and maybe 100 feet deep, with sandblasted brick on the walls which was popular at the time, and the whole place had a drop ceiling. The stage was on the left and it was carpeted with mirrored tiles above the stage, which caused Les McCann to look up from the piano one night and say, “This reminds me of some bedrooms I’ve been in.”

Puzzo was a jazz fan. Primarily for his own enjoyment, he installed a simple audio recording system to record the performances: two microphones suspended from the ceiling above the stage, with cables running to an Ampex reel-to-reel deck in his office (this is the setup on which this recording was made.) He was more supportive and personable than most venue owners, and generally well-liked. When Miles Davis came through, Puzzo would join him at the boxing gym. When some local players, like saxophonist Carlos Ward, could not afford the cover, he allowed them entrance. “He always treated me with respect and was very nice to me,” recalls bassist David Friesen. “I don’t know if Charlie was an ex-boxer or not, but that vibe was there.” Friesen and Ward were of the same generation based in Washington state near Seattle—as well as guitarists Larry Coryell and Ralph Towner. They were all future jazz players coming of age at the time, for whom The Penthouse served as a place to listen and learn from the legends; Friesen performed there as a member of the house band led by Joe Brazil.

With limited experience working with bands, Puzzo had enlisted a local talent booker—Bill Owens of Northwest Releasing Corporation—to secure national acts for the club. Owens also brought pop acts and theatrical companies to the city. “Everything from the Lipizzaner Stallions to the Black Watch drum-and-bugle corps,” adds Wilke, “Bill had pretty good connections and was pretty hip jazz-wise.” Dizzy Gillespie, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Jimmy Smith, Carmen McRae, Bill Evans, Stan Getz, and George Shearing were among the heavyweights The Penthouse presented. The Saturday before Coltrane arrived, Cannonball Adderley had closed out two weeks there; Oscar Peterson was scheduled for the week after.

Coltrane’s impending arrival was marked by a number of Seattle jazz fans and musicians, including Ward, who would soon move to New York City to launch his own career; Friesen, who had first heard and met the members of the Classic Quartet in 1963 in Copenhagen while serving military duty overseas; and the Detroit-born saxophonist and educator Joe Brazil, a recent transplant to Seattle, who, like Garrett, had befriended Coltrane during his years in Miles’s employ. In 1989, Brazil told jazz journalist and historian Paul de Barros of befriending Coltrane when he passed through Detroit: “We’d hang out, chat, talk, discuss music and that kind of thing…usually, four or five of us saxophone players would be together. It’d be Yusef [Lateef], Joe Henderson, myself, [Kenneth] “Koko” Winfrey and Trane.” Brazil added: “Trane was always absorbing as well as giving.”

When Coltrane played Detroit with his first touring quartet in 1961, he stayed at Brazil’s home. And when the saxophonist headlined The Penthouse, Brazil’s lineup of Seattle musicians—which included Ward and Friesen—opened each set. It’s no stretch to assume Coltrane was aware of Brazil’s propensity for recording jazz sets, and that like Coltrane, he possessed a portable Wollensak reel-to-reel recorder (nonetheless, it’s apparent Brazil’s tapes utilized the club’s two-mic/Ampex setup).

On its entertainment page for the week of September 27, The Seattle Times listed a variety of evening options, most of the dinner-and-show variety: trumpeter Jonah Jones was at The Olympic, the singer/actor Dennis Morgan was working the Edgewater Inn, and local pianist/entertainer Frank Sugia was with his trio at the Casa Villa restaurant. On Friday night, one could attend a “Folk-Rock and All-Cause Music Festival” headlined by Barry McGuire at the Seattle Arena, and tickets were being advertised for next week’s concert by Louis Armstrong and his All Stars at the Seattle Center Coliseum for $1.60.

“Jazz Star” John Coltrane was listed opening at The Penthouse. “At that time it was a buck for a beer or a glass of wine,” Wilke reports. “Prices were pretty reasonable and the cover charge was too.” Coltrane’s run was popular enough to fill the club most nights, recalls Friesen: „I remember a line every night the whole week, and people going by the Penthouse in the rain—you know it’s always raining in Seattle—and pressing their faces against the window.”

A Seattle Times review of Coltrane’s opening night, written by Ed Baker and published on Wednesday, certainly helped. Baker penned a generous, non-judgmental appraisal of Coltrane’s music—focusing on the empirical, and explaining the music through a conversation with the club’s booker: “Owens whispered to friends at a ringside table, This will be like nothing you ever heard…modern jazz has to go new ways. This is Coltrane’s way, taking a few notes and being free. Maybe this isn’t the way jazz will go; maybe it is. Anyhow, it’s an experience”.

Baker agreed with Owens’s assessment. “It’s an experience—the most unusual experience modern jazz has to offer.” He also noted that the Penthouse had been expecting Coltrane with his quartet; they hadn’t been informed of the recent additions. Many were taken aback, knowing Coltrane through past recordings and appearances.

“Frankly, it caught me by surprise,” recalls Wilke of the night he broadcast the group’s set. “I mean I had heard Coltrane take long solos with Miles, but this was the first gig on the road with Pharoah Sanders and the two bass players and Pharoah stepped up, and he started free right from the start.” Wilke continues:

Probably after 20 minutes or so, Coltrane got off the stage while the band kept playing and came over and pointed to the headphones I had on. I took them off and gave them to him. He listened for awhile and nodded his head. Then he leaned over and said, “This may go longer than half an hour.” He knew we had to do a radio ID and my mic was hooked up to the club’s system so I couldn’t do it that way. I said, “That’s okay, we have a prerecorded announcement at the radio station.” Then they went for two and a half hours nonstop!

The long sets not only disrupted the club being able to turn the house between sets, but also the flow of drink orders, which did not sit well with Puzzo. He spoke directly to Coltrane that first evening, and for the rest of the run the sets returned to a predictable length, while the tunes remained extended. Wilke also recalls a conversation with the owner towards the end of the week. “Charlie said, give me the Jimmy Smith crowd any time—they order champagne by the bottle; the Coltrane people buy one beer and then sit there all night!”

All agreed: the music was mesmerizing. It demanded a different level of attention and it clearly served a purpose beyond social lubrication. But not everybody was convinced. “I remember Jim Wilke at the Penthouse when Trane was playing there,” Brazil recalled in his interview with de Barros. “And he said, ‘You know he sounds like he’s angry to me.’ And I said, ‘Well no, it’s not anger. I think what happens is you’re coming from a perception of where you are at the moment.’“

Some people may look at that music as hostile because the way jazz musicians are…people be looking at them and sometimes they’re going through various gyrations. You’re just creating to the fullest of your thing. I mean you’re in a state of being where you’re really exhilarated. But when you’re really involved in the music, you’re not aware of the audience or self or whatever because everything is clicking as a harmonious group.

Friesen’s reaction echoes Brazil’s:

I remember sitting there listening to Coltrane. For the first maybe ten or fifteen seconds of each set I noticed McCoy and Elvin and Jimmy and Coltrane. And then when you augment it with other players, it doesn’t mean it’s going to be better. It will be different. I noticed them each alone, but after that they each became less and the music became more. The music raised itself above who they were. It was a collective sound. Once Jimmy told me something about playing in that band. He said, it’s very complicated but once you’re up there, you’re listening and everything you’ve learned in the practice room teaches you to take your eyes off yourself. That was my experience with that band: everyone was listening and responding creatively to what the other one was doing. Their eyes were on the music. Coltrane was the epitome of that concept in my opinion.

Coltrane’s week in Seattle was focused on his nightly performances at The Penthouse, and during the day, hanging and talking with the band and friends—like Joe Brazil. The conversation focused on music, the politics and events of the day, and spirituality—and the ideas and spirit of those discussions would flow into the evening. Sanders recalls Coltrane was traveling with a copy of the Baghavad Gita and referred to it—and eventually passed it on to Sanders. Carlos Ward retains the memory of a copy of “The Bible or some religious book backstage at the Penthouse. It was big, and very impressive.” Brazil recalls: “We were reading the Bhagavad Gita. I had about ten versions of the Gita, the Hindu Bible, and Trane was interested in some of those versions that I had. Now I never did know really what his background was as far as studying different philosophies and religion, but we’d start chanting ‘Om’ one day at the gig [while] we’re playing.”

Coltrane had time to sit and do it all, and inspired by what he was hearing in his new sextet, he engaged (at his own expense) local recording engineer Jan Kurtis to record all the sets on Friday at The Penthouse (a total of three-and-a-half hours of music first edited and released as the double LP Live in Seattle on Impulse in 1971; in 1994, an expanded CD edition was issued.) The next morning Coltrane booked time in Kurtis’s recording studio—Camelot Sound—to record the sextet, with the addition of Joe Brazil on flute. They recorded an almost half-hour composition titled Om, which the group opened and ended with a spoken incantation from the Bhagavad Gita.

Saturday evening, October 2, was Coltrane’s last night in Seattle. After an advertised matinee from 3 to 7pm that included a set by Joe Brazil’s group, the sextet took the stage, and Carlos Ward, who had played with Brazil, remained. Brazil, who had recorded his own group on the club’s Ampex, prepared to record the next set on the same 7” reel (as he was recording on only two of the tape machine’s four tracks, which allowed him to double the amount of music being taped on any reel; he would eventually have to flip the reel and start a new reel to capture the rest of the next set.) New patrons were arriving and many in the crowd were still talking; with no formal emcee introduction or comment from the band, Coltrane began to blow the beatific benediction that opens A Love Supreme.

Once you become aware of this force for unity in life, you can’t ever forget it. It becomes a part of everything you do . . . my conception of that force [in music] keeps changing shape. My goal in meditating on this through music, however, remains the same. And that is to uplift people as much as I can. To inspire them to realize more and more of their capacities for living meaningful lives. Because there certainly is meaning to life.

—John Coltrane to Nat Hentoff, late 1965

Memories fade, as do the echoes of one particular, 75-minute set on a Saturday night: one set out of a week of performances, witnessed by almost three hundred patrons (the official capacity at The Penthouse was approximately 275.) It had constituted the entirety of the A Love Supreme suite, extended with solos and interludes, more than twice the duration of the original studio recording. To three Seattle musicians, the experience left a permanent imprint. “It was a gift, Coltrane coming up to Seattle.” says Ward. “That night sent out some new messages.” “All week long the music was very intense, very spiritual,” Friesen adds.

I’ve always pursued the spiritual aspect of the music and I still do. I remember sitting with Coltrane during one break that week and John telling me his grandfather had been a minister and that he came from a Christian background, and wished he had pursued a religious path earlier and how drugs had interfered with that. Being as great as Coltrane was as a musician, what touched me was the way he treated other people. He showed mercy and kindness to people from what I could see around me for the week that I was there.

Brazil felt a level of intention transcending the world of cover charges, drink minimums and set-lengths. “I think Trane—and Dizzy and Miles and whoever—are trying to reach a certain sound that will reach a certain center of consciousness that could make people more aware, more friendly, better, make the earth a little bit better.”

In 1965, Seattle liquor licenses did not permit sales on Sunday, so Saturday night brought Coltrane’s engagement at The Penthouse to an end. Within a day or two, the group—with two new members—departed for a long, unrushed drive down to Los Angeles.

—Ashley Kahn, 2021

Ashley Kahn is a Grammy-winning American music historian and producer. He is the author of A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album; The House That Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records; and other titles.

Radio

Media Promotion (Promotion Süd, West & Nord)

Rosita Falke

info@rosita-falke.de, Tel: 040 – 413 545 05

Musicforce

Anja Sziedat (Promotion Berlin / Ost)

anja.musicforce@gmail.com, Tel: 030 – 419 59 615, Mobil: 0177 – 611 5675

Impulse! Records / Universal Music

CD 06024 3849997 / 2-LP 06024 3849998

NEUER VÖ: 22.10.2021