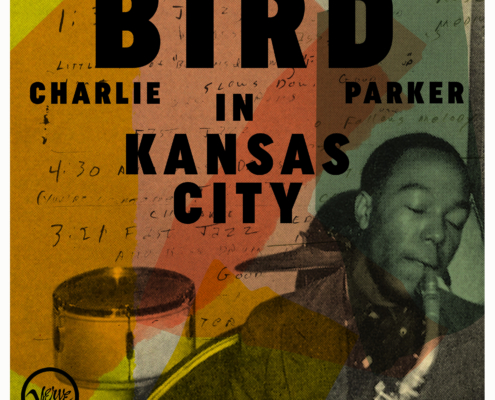

CHARLIE PARKER – BIRD IN KANSAS CITY

FEAT. PREVIOUSLY UNKNOWN & RARE RECORDINGS FROM 1941-1951

Ohne Frage ist CHARLIE PARKER neben John Coltrane nicht nur einer der bedeutendsten Saxophonisten des Jazz, sondern auch einer der stilprägendsten Musiker der Neuzeit. Von den Aufnahmen der kurzen Schaffensphase „Birds“ gibt es zahllose Veröffentlichungen, die zu den wichtigsten Dokumenten des Jazz zählen.

Die Entdeckung unveröffentlichter Parker-Aufnahmen gilt stets als Sensation, daher dürften auch diese aus den Jahren 1941-1951 ein großes Echo auslösen. Die meisten davon waren bislang noch nie zuvor zu hören und von einigen war unbekannt, dass sie überhaupt existieren.

Zusätzlich zu zwei unveröffentlichten 78er-Singles mit der Jay-McShann-Band sind auf BIRD IN KANSAS CITY zwei private Parker-Sessions zu hören, die im Haus seines Freundes Phil Baxter und im Studio von Vic Damon entstanden.

Für alle Freunde des klassischen Jazz und der atemberaubenden Improvisationen „Birds“ ist diese CD mit ausführlichem Booklet und 140g-LP mit neuen Linernotes auf dem Innersleeve unverzichtbar.

TRACKLIST

- Bird Song #1 (Charlie Parker)

- Bird Song #2 (Charlie Parker)

- Bird Song #3 (Charlie Parker)

- Cherokee — Phil Baxter version (Ray Noble)

- Body and Soul — Phil Baxter version (Johnny Green–Edward Heyman–Robert Sour–Frank Eyton)

- Honeysuckle Rose (Fats Waller–Andy Razaf)

- Perdido (Juan Tizol)

Personnel: Charlie Parker (alto sax); unknown (bass); unknown (drums)

Recorded: July 1951 at the home of Phil Baxter in Kansas City, MO

- Cherokee — Vic Damon version (Ray Noble)

- My Heart Tells Me (Harry Warren–Mack Gordon)

- I Found a New Baby (Jack Palmer–Spencer Williams)

- Body and Soul — Vic Damon version (Johnny Green–Edward Heyman–Robert Sour–Frank Eyton)

- Margie (Con Conrad–J. Russell Robinson–Benny Davis)

- I’m Getting Sentimental Over You (George Bassman–Ned Washington)

Tracks 1–4: Personnel: Charlie Parker (alto sax); Efferge Ware (guitar); Edward “Little Phil” Phillips (drums)

Recorded: probably June 1944 at Vic Damon’s Transcription Studios in Kansas City, MO.

Tracks 5 & 6: Personnel: Jay McShann and His Orchestra: Jay McShann (piano, director); Orville Minor (trumpet); Charlie Parker (alto sax); Joe Coleman (vocals); and probably Bernard Anderson, Harold Bruce, Joe Baird (trombone); John Jackson (alto sax); Harry Ferguson, Bob Mabane (tenor sax); Gene Ramey (bass); Gus Johnson (drums)

Recorded: February 6, 1941 in Kansas City, MO.

LINERNOTES

This new set of Charlie Parker rarities, Bird in Kansas City, reveals his transformation as a musician. Recorded between 1941–1951, these recordings chronicle Bird’s evolution from a blossoming soloist with the Jay McShann band into a brilliant improviser who dominated after-hours jam sessions. It is significant that they were recorded in his hometown of Kansas City.

Parker had mixed emotions about Kansas City. After leaving in 1941, he never lived there again. Yet, while traveling across the country, he often stopped off in Kansas City to spend time with friends and his mother, Addie. His ambivalence is understandable. Like most cities in the United States at the time, Kansas City was racially segregated. Growing up there, Charlie blew past racial barriers. As a budding musician, he jammed with white musicians. Socially, he enjoyed the company of white friends. While Charlie moved easily between the two worlds, he often encountered reminders of segregation.

Originally, a trading outpost at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, Kansas City, Missouri grew into a cosmopolitan center for commerce and entertainment, known as the Paris of the Plains. A local Democratic political machine headed up by a burly Irishman, Tom Pendergast, fostered vice and corruption. Gambling was pervasive throughout the city. In the red-light district on 14th Street, scantily clad women lounged in illuminated storefront windows. When johns walked by, they grabbed nickels and began furiously tapping on the windows. During Prohibition, it was business as usual in the saloons, night clubs and bars, providing ample employment opportunities for musicians from the southwestern territories. Mary Lou Williams recalled fifty clubs featuring live music in a six-block area between 12th and 18th Streets where Bennie Moten, Buster Smith, Lester Young, Count Basie, Hot Lips Page and a host of other jazz greats were pioneering a new, swinging style of jazz and battling in all-night jam sessions.

The Kansas City metropolitan area straddles the state line of Missouri and Kansas. Charlie was born in Kansas City, Kansas and came of age as a man and musician in Kansas City, Missouri. On August 29, 1920, Dr. J.R. Thompson delivered him in the family’s two-room apartment above the Kesterson and Richardson grocery store at 852 Freeman, in the heart of the African American community. His father, Charles, Sr., travelled widely as a railroad porter. His mother, Addie, tended to the household and doted on Charlie, dressing him in the finest clothes. He attended Douglass School, named for abolitionist Fredrick Douglass.

In 1927, the Parker’s moved to Kansas City, Missouri. His father worked as a janitor in an apartment building in a middle-class white neighborhood in mid-town. The family settled into a spacious apartment at 3527 Wyandotte. Charlie attended Penn School in Westport. Named after Quaker William Penn, Penn was the first school established west of the Mississippi River to educate African Americans. He first picked up the alto saxophone in fifth grade when the school district initiated a music program.

When his parents separated in 1931, he and Addie moved to a house at 1516 Olive St. In 1932, Charlie enrolled in Lincoln High School where he played in the band and orchestra. The only high school for African Americans in the Kansas City School District, Lincoln supported a strong music program. Addie worked nights as a custodian at Western Union located in Union Station, Kansas City’s sprawling train station. After Addie left for work in the evening, Charlie continued his musical education participating in cutting contests in the alleyways behind the clubs between 12th and 18th Streets. These cutting contests were musical rites of passage for young musicians.

While launching his career, Parker suffered several setbacks including an incident in the spring of 1936, when he sat in on a jam session at the Reno Club, where the Count Basie band held court. When he faltered while soloing on “Honeysuckle Rose”, drummer Jo Jones expressed his displeasure by throwing a cymbal at his feet. Publicly humiliated, Charlie retreated to his mother’s house where he practiced incessantly and mastered his instrument.

Another setback occurred on Thanksgiving Day 1936, while Charlie traveled with a union band for a gig at Musser’s Tavern, five miles south of Eldon, Missouri. Enroute, the car he was traveling in hit a slick spot in the road and flipped over five or six times. The wreck broke his back and several ribs. While recuperating at home, Charlie developed a taste for narcotics. He struggled with substance abuse the rest of his life.

Despite these challenges, Charlie soon emerged as an in-demand soloist. After passing through the ranks of the Buster Smith and Harlan Leonard bands, Charlie joined the Jay McShann band. A laid-back band leader, pianist McShann tolerated Charlie’s unreliability. His musical leadership of he reed section pleasantly surprised McShann. “What really helped was having Bird in that big band,” McShann explained in a 1997 interview. “When we got to the point when we had five saxophones. When Bird was in the section, you would see him turn, especially on those head tunes he would be giving this cat his note. He’d give him the note he wanted him to make.” The McShann band quickly emerged as the leading band in Kansas City and the surrounding area.

In late-January 1941, the band’s manager, John Tumino, bought a disc cutting machine to make home recordings of the band in preparation for an upcoming recording session for Decca Records in Dallas, Texas. On February 6, he recorded the band performing two standards: “Margie” and “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You”. These spontaneous recordings capture the band in transition and feature two solos by Charlie. On “Margie”, after a brief introduction, the reed and brass sections state the melody accented by riffs followed by Joe Coleman’s mid-range vocal. Following a band chorus, Orville “Piggy” Minor delivers a fiery upper register trumpet solo. In the out chorus, McShann takes a solo highlighted by chord substitutions followed by an understated, bluesy eight bar solo by Bird.

Jay McShann and the rhythm section kick off “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” with an eight-bar introduction. Joe Coleman follows with a thirty-two-bar vocal rendered in the popular style of the day. Charlie then steps in with a brilliant, lyrical thirty-two bar solo capped off with a four-bar codetta. He peppers the opening bars of his solo with 32nd note flourishes. His lilting solo then glides along propelled by fleet runs of 16th notes. Parker’s strikingly original solo reveals his formidable technique and maturity as a soloist.

In April 1941, the McShann band travelled to Dallas where they recorded six selections. Several months later, Decca released a pair of blues from the session: “Confessin’ the Blues” backed by “Hootie Blues”. “Confessin’ the Blues” hit big nationally, creating a strong demand for the band. After playing a summer engagement at Fairyland Park, Kansas City’s premiere amusement park, the McShann band relocated to New York City. Charlie loved the excitement of New York and, except for an ill-fated jaunt to California, lived there the rest of his life.

After leaving the McShann band, Charlie served a short stint in the Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines band before joining the Billy Eckstine Band. While working with the Eckstine Band, Bird found a musical kindred soul in trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Feeling constrained by the big band, Parker and Gillespie formed a small combo. Together, they pioneered bebop, a revolution in jazz.

Parker soon emerged as a band leader. A series of critically lauded recordings and concerts established his reputation nationally. Charlie’s acclaim soon caught the attention of Jazz at the Philharmonic impresario, Norman Ganz. Jazz at the Philharmonic, launched four years earlier in Los Angeles, evolved from a free-wheeling jam session into an institution that played auditoriums and concert halls across the country. Granz paid musicians well and made sure they were respected as musicians and individuals.

On April 18, 1948, Charlie joined Jazz at the Philharmonic for a 26-day tour across the nation. He shared the spotlight with Sarah Vaughan, a popular vocalist. Jazz at the Philharmonic played two dates in Kansas City at the Municipal Auditorium. On Tuesday, April 27, Jazz at the Philharmonic played for a white audience in the art deco Music Hall followed by a date the next night at cavernous Auditorium for a racially mixed audience. During the concert, Parker dazzled the hometown audience with his fiery solos. The Kansas City Call reported that “Charley [sic] ‘Yardbird’ Parker, a Kansas City, Kas., [sic] born alto saxist was terrific and won resounding applause for his Be-bop mastery. He heated up the house to the boiling point every time he appeared on stage. The guy actually crowded so many eighth and sixteenth notes into a measure that it seemed his horn would burst.”

While in Kansas City, Charlie and trumpeter Red Rodney, a new member of his group, stayed at Addie’s home. After hours, they sat in with Bud Calvert and His Headliners at the Playhouse, a popular roadhouse located at 2240 Blue Ridge, just outside of the city limits. The Calvert band played from 9:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. Tenor saxophonist Charlie White and other white musicians who had jammed with Parker earlier in Kansas City stopped by to renew old acquaintances.

Coming of age musically at the same time, White and Parker became fast friends. The two maintained their relationship after Charlie left town with the McShann band. During Charlie’s appearance in Kansas City with the Billy Eckstine Band in June 1944, White arranged for a recording session at Vic Damon’s Transcription Studios at 1221 Baltimore. Damon, a pioneering engineer, established his recording studio in 1933. He soon emerged as the top recording engineer in town. Catering to the masses, Damon charged 50 cents per side with a six-minute minimum. Long-time musical associates, drummer Edward “Little Phil” Phillips and guitarist Efferge Ware joined Charlie for the session.

Little Phil, who was a steady timekeeper, had played with Charlie in guitarist Lucky Enois’ band at Tootie’s Mayfair, a popular nightclub at 79th and Wornall Rd. Trumpeter Buddy Anderson and other musicians considered this to be first group to play Bebop. Ware and Parker jammed together at late night sessions at Parade Park near 18th and Vine. Later, they worked together in the Harlan Leonard Band. The three old friends came together easily for the session. Bird called the tunes, drawing from familiar repertoire.

With Parker taking the lead, the band recorded: “Cherokee”, “My Heart Tells Me”, “I Found a New Baby” and “Body and Soul”. Ray Noble’s “Cherokee” was one of Bird’s favorite songs. Whenever he showed up late for a gig, he would make a grand entrance through the front door playing “Cherokee”. Taken at a bright tempo, Charlie takes wing with a melodic solo that deftly navigates the song’s challenging chord changes. Charlie tenderly embellishes the melodies of the two ballads, “My Heart Tells Me” and “Body and Soul”. Charlie pays homage to Lester Young by quoting “Tickle Toe” and “Shoeshine Boy” in his rendition of “I Found a New Baby”. At the end of the session, White retained the discs for safe keeping.

Distracted by their revelry in Kansas City, Parker and Rodney missed their ride out of town with Jazz at the Philharmonic. Charlie White flew them in his private plane to the next Jazz at the Philharmonic stop in St. Louis. During the trip, Rodney found that White, like Parker, delighted in living close to the edge. “We were with Norman Granz, JATP and had played K.C. and stayed overnight at Bird’s mother’s home,” Rodney recalled. “The fellow named Charlie White was an airline pilot (for T.W.A.) and also had his own plane — with which he offered to fly us to St. Louis for the next concert. During the very rough and bumpy flight in the small aircraft Bird decided he would like to operate the plane and Mr. White allowed it [Parker to take the controls] over my screaming protests.”

In July 1951, Charlie returned to Kansas City under considerably different circumstances. Earlier that year, he had been busted for possession of heroin. The judge gave him a stern warning and a three-month suspended sentence. As a result of his bust, Parker lost the cabaret card that allowed him to work in New York City nightclubs and cabarets. At the same time, New York State cracked down on drug use at Birdland, the Apollo Theater and other venues in New York.

Unable to work in New York City, Charlie retreated to Addie’s home in Kansas City where he could make some money gigging around town. He could always depend on hustling up a gig on short notice at Tootie’s Mayfair, a nightclub located just outside the city limits, in an area known as being ‘out in the county’. Operating outside the city’s southern boundary allowed the Mayfair and other clubs in the area to evade liquor laws and stay open all night. A former police detective, Tootie Clarkin opened his namesake club at 7952 Wornall Rd. in 1940. A popular nightspot, the Mayfair Club featured local and national acts with three shows nightly. As the city’s southern boundary moved further south, Tootie relocated his club to stay out of the reach of the police. In early 1951, Tootie’s moved to 7420 E. US Highway 40. Charlie opened at Tootie’s on July 11th for a two-week engagement, playing with a pickup band.

During his off hours, Charlie spent time with friends at the home of Phil Baxter. A barber by trade, Phil worked at the Front Page Barber Shop, located at 1709 Grand, just north of the Kansas City Star building. Like Parker, Baxter loved to party. A hipster with a large circle of friends, Baxter threw elaborate parties in his home at 2008 Kensington Avenue, in the heart of Kansas City’s Eastside. Baxter’s wife Kathleen and young son Barry helped host the soirees. Charlie, who had an uncanny ability to relate to children, adopted Barry as his godson.

Charlie usually arrived with great fanfare, driven by a preacher in a Cadillac. During the late-night festivities, he jammed with all comers ranging from ambitious students to veterans of the Kansas City scene. Musicians and friends mixed freely in the Baxter residence. Ray and Addie Crawford who were close friends of the Baxters often attended the late-night sessions. Their daughter Judy and Barry were close friends. Crawford, an engineer at Pratt and Whitney, a local military contractor, operated a recording setup equipped with microphones, a disc cutting machine and wire recorder in the basement of his home.

At Baxter’s urging, Crawford brought a wire recorder to one of the parties to record Bird. A precursor to open reel tape, wire magnetic recorders recorded audio to a fishing-line-thin steel wire wrapped tightly around a small metal spool. Unlike commercial disc cutting machines that were limited to cutting three minutes of audio per side of a 10” disc, wire recorders could record up to one hour of audio. Crawford carefully set up his portable rig and captured Charlie happily soloing at the top of his game.

According to alto saxophonist Bobby Watson, “These recording find Charlie in a relaxed, intimate mood playing looser with the changes. He also plays some upper extensions of the chords that are not normally heard on his classic recordings.”

Accompanied by a bass player playing a straight walking bass line, Charlie launches into a spirited improvisation, here titled “Bird Song #1”, that quotes “Twisted”, “Buttons and Bows” and “Pick Yourself Up”. The blistering solo that follows a false start on “Bird Song #2” features quotes from his own compositions “Kim” and “Moose the Mooche”. In a nod to his mentor, Lester Young, Parker then jams off the changes of “Lady Be Good” on “Bird Song #3”. On the next track, Charlie plays “Cherokee”. He follows with “Body and Soul”, switching to double time at the bridge. Spirited, playful renditions of “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Perdido” wrap up the session. Bird punctuated each selection with a musical coda to let the bassist and recording engineer know that he was wrapping up the tune. After the session, Baxter tucked away the wire for safe keeping. Later, realizing the fragile nature of the wire, he had open-reel copies made for safe keeping.

Shortly after closing out at Martin’s, Charlie returned to New York City. The next few years marked a decline in his mental and physical health. Unable to sustain a working group or perform in New York City clubs, Charlie resumed touring nationally, playing with local pick-up bands. Along the way, he alienated club owners, booking agents and musicians. The pressure of constantly touring fueled his already prodigious consumption of alcohol and heroin, triggering his ulcer and other health issues.

The lyrics of King Pleasure’s 1954 hit vocal version of Bird’s song “Parker’s Mood” foreshadowed his death and return to Kansas City. Understandably, after hearing Pleasure’s version of his blues classic, Charlie begged his wife Chan not to bury him in Kansas City. Unfortunately, Pleasure’s vocal version proved to be prophetic.

On March 12, 1955, Charlie passed away in the suite of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, in the Hotel Stanhope, located on 5th Avenue across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As Chan made plans for a simple ceremony and burial in upstate New York, Addie and Charlie’s third wife Doris claimed his body and made arrangements for an elaborate funeral in Harlem. Addie and Doris accompanied his body back to Kansas City where they buried him under a tree at the top of a hill in Lincoln Cemetery, Kansas City’s burial ground for African Americans.

Chuck Haddix is the author of Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker, University of Illinois Press and co-author with Frank Driggs of Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop — A History for Oxford University Press. He is also Curator of the Marr Sound Archives at the University of Missouri–Kansas City and host of the Fish Fry on KCUR, Kansas City Public radio station.

Weitere Infos in unserem Presseportal unter

https://journalistenlounge.de – bitte dort über den Genrefilter „Jazz“ anwählen!

PR Radio

Universal Music Jazz (Deutsche Grammophon GmbH)

Mühlenstr. 25, 10243 Berlin

Verve / Universal Music

LP 06024 6804734 / CD 06024 6804735

VÖ 25. Oktober 2024