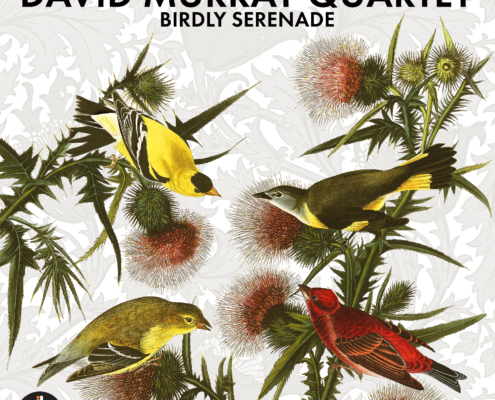

David Murray – Black Bird Singing

- Birdly Serenade 5:23 Feat. Ekep Nkwelle

(Music by David Murray/Lyrics by Francesca Cinelli)

- Bald Ego 7:01

(David Murray)

- Song Of The World (for Mixashawn Rozie) 9:43

Feat. Ekep Nkwelle

(Music by David Murray/Lyrics by Francesca Cinelli)

- Black Bird’s Gonna Lite Up The Night 8:57

(David Murray)

- Nonna’s Last Flight 7:20

(David Murray)

- Capistrano Swallow 4:24

(David Murray)

- Bird’s The Word 7:52

(David Murray)

- Oiseau de paradis 10:29 Feat. Francesca Cinelli

(Music by David Murray/Lyrics by Francesca Cinelli)

David Murray: Tenor Saxophone, Bass Clarinet

Marta Sanchez: Piano

Luke Stewart: Bass

Russell Carter: Drums

Ekep Nkwelle: Vocals

Francesca Cinelli: Spoken Word

David Murray steht seit fast 50 Jahren an der Spitze der internationalen Jazzszene. Mit seinen verschiedenen Ensembles – von seinem Octet über das World Saxophone Quartet bis hin zu seiner Big Band – hat er Modern Jazz und Avantgarde mit Einflüssen der gesamten Bandbreite des Jazz verbunden und das Genre maßgeblich mit vorangetrieben.

Mit Gründung seines neuesten Quartetts im Jahr 2024 hat sich David Murray als eine der führenden Stimmen seiner Kunst zurückgemeldet. Für sein Debütalbum auf Impulse! Records lassen Murray und sein Quartett – die Pianistin Marta Sanchez, der Bassist Luke Stewart und der Schlagzeuger Russell Carter – sich von Musik inspirieren, die älter ist als die Menschheit – Vogelgesang.

Das Album „Birdly Serenade“ ist ein Teil des aufsehenerregenden, musikübergreifenden „Birdsong Project“ (www.thebirdsongproject.com), sechs der acht Originale entstanden in einem Künstler-Retreat in den Adirondack Mountains, inmitten von Seen, Wäldern und endlosem Himmel.

Am Anfang des Schreibprozesses standen drei Gedichte von Francesca Cinelli, die auf dem letzten Titel des Albums auch mit einer Spoken-Word-Performance zu hören ist. Die Gedichte erforschen die Themen Flug, elementare Natur und was es bedeutet, ein Mensch zu sein.

„Birdly Serenade“ wurde im berühmten Van Gelder Studio, der spirituellen Heimat von Impulse! Records, aufgenommen und enthält acht von Murray geschriebene Kompositionen, von denen zwei vom aufstrebenden Gesangsstar Ekep Nkwelle interpretiert werden.

LINER NOTES Black Bird Singing

As a species, we make one hell of a racket. That’s on us. Industry ushered in the age of noise: presses clattering, tools banging, engines revving, steel-clad birds roaring dawn to dusk over the roofs of working communities short on sleep. How could any blackbird compete with that?

When during the covid-19 pandemic the daily racket called “civilization” turned inward, among the changes most audible was the return of birdsong. In places rural, urban, and in-between, sounds familiar or forgotten took on a new density: screeches, squawks, trills, and above all, melodious song. The cadence, and even the pitch, of some birdsongs came back altered, as if to signal to our undiscerning ears: listen to us for a change. The birds’ words.

Birdsong has a musical history nearly as long as the history of music itself. In Sufi devotional singing of the Middle East, birds were said to converse in a mystical divine language. Secular songs of medieval and Renaissance Europe celebrated the nightingale and the lark. In Asia, instrument makers and players sought out the intermediary pitches present in birdsong, as well as the ability, shared by some avian species, to play two pitches at once. Modern composers seeking liberation from scales and modes wove simple calls or complex songs into their works, from Respighi in his suite Gli uccelli (1928) to Messiaen in his Catalogue d’oiseaux for solo piano (1956-1958).

“Hot” jazz, heavy on syncopation and brass, was associated by its early critics with machine-age industrialism, and written off, in contrast to church-based spirituals, as “noise.” A certain Bird, born in Kansas City in 1920, settled all that. The composer of “Ornithology” likely knew that in French, the same word, le bec, designates a mouthpiece and a bird’s beak. He also may have known that the Greek pan flute was called a syrinx – as any ornithologist (of the other sort!) will tell you, the y-shaped organ below the trachea that allows birds to vocalize.

Innovator Eric Dolphy learned firsthand the relevance of birdsong to improvisation: speaking with John Coltrane and writer Don DeMicheal in the April 12, 1962 issue of Downbeat, he confided that imitating birds was part of his development. “At home [in California] I used to play, and the birds always used to whistle with me. I would stop what I was working on and play with the birds.” They pushed Dolphy to discover quarter-tones on the flute: “Birds have notes in between our notes”.

David Murray hears it, and plays it, in a similar way. “A whole world is up there if you can find how to get to it,” he says. And if Murray, unlike Dolphy, never practiced alongside birds growing up in the Bay Area, early study of flute and piccolo attuned him to the upper registers of what would become his signature horns, tenor saxophone and bass clarinet. Murray feels Sun Ra was right to conduct on his own terms the search for a “universal language”: as the Arkestra’s bandleader said in the 1980 documentary A Joyful Noise, “I’m just like the birds, they sing. Those who like, can listen.” For Murray, that statement retains a political edge, Sun Ra’s other-worldliness notwithstanding. Nature shows us the way. “The snake is gonna bite. The tiger’s gonna pounce. The bird’s gonna sing.”

And sing it does. For this installment of the Grammy® award-winning Birdsong Project, producers Randall Poster and Stewart Lerman gave Murray free reign. Six of the eight originals took shape at an artists’ retreat in the Adirondacks, amidst lakes, forests, and endless sky. At the start of the writing process were three poems by Francesca Cinelli. Each explores, via themes of flight and elemental nature, what it means to be human. On the 3/4 “Birdly Serenade,” guest vocalist Ekep Nkwelle swoops down from soprano to a warm alto register, tracking the “tremolos of the diving bird” through the mist to discover “swirling minnows” below, while Murray’s tenor offers cool comment. The plangent “Song of the World,” also featuring the prodigiously gifted Nkwelle, is a luminous portrait in motion of its dedicatee, the Indigenous musician, craftsman, and educator Lee Mixashawn Rozie. Taken on wood-toned bass clarinet, it evokes the spiritual cleansing offered to those who approach nature with quiet humility and respect. The album’s closer, “Oiseau de Paradis,” is performed spoken word by Cinelli, in a voice now sultry, now fervent. Its consonant-rich French text describes the courage needed to find space in relationships: what can a coat of feathers reveal of the heart that beats within? A heavily swung rhythm in two yields to a syncopated, trancelike 6/4, with Murray’s blistering tenor solo and Sanchez’s layered motifs preparing the reprise of the text, down to its final “pêcheur volatile,” or kingfisher. (Folks at the R.I.A.A., take note: a foc is the mariner’s term for a foremast jib. Really!)

It’s Murray’s conviction that whether in concert or on records, an ensemble should “acknowledge each phase” in the history of the music. This isn’t meant in a spirit of reconstruction or revivalism, but to assert the life-affirming power of Black musical styles, from blues to deep funk and free improvisation. Here, five instrumentals give balance to the vocal numbers and let the quartet stretch out on its second recorded outing. Hearing Murray pay his respects to mid-century greats Lester Young, Ben Webster, and Hal Singer in the twelve-bar blues “Bald Ego,” you’d swear you walked into a smoke-filled jazz joint in Chicago circa 1950, a stuffed parrot perched above the liquor rack. Likewise rooted in history is “Bird’s the Word,” a near contrafact of Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” whose danceable major-chord bounce recalls Freddie Redd or Jackie McLean.

Two exploratory tracks shake the wood rafters at the Van Gelder studios, hallowed ground if ever there was. Improvised at the sessions, “Black Bird’s Gonna Lite up the Night” features dense textural interplay out of which melody and rhythm ebb and flow, while “Capistrano Swallow,” centered on Sanchez’s clusters, jabs, and fleet runs, recalls Murray’s trips to the famed mission outside L.A. where nesting birds returned each May. And wherever would we be without infectious groove? For “Nonna’s Last Flight,” rhythm mavens Stewart and Russell lock in tight to let the elder statesman soar on a riff. It’s the tune Eric Dolphy might have dreamt of playing had he lived into the era of funk.Says Murray of our embattled feathered friends, “if I’m a bird, I’m gonna sing regardless of what you humans do or the situations you put us in.” He sure got that right. The black bird has sung. Derek Schilling, February 2025

Weitere Infos in unserem Presseportal unter

https://journalistenlounge.de – bitte dort über den Genrefilter „Jazz“ anwählen!

PR Radio

Universal Music Jazz (Deutsche Grammophon GmbH)

Mühlenstr. 25, 10243 Berlin

Impulse! Records / Universal Music

CD 00602475915911 / LP 00602475915928

VÖ: 25.04. 2025

** SPERRFRIST BIS 14. MÄRZ 2025 **