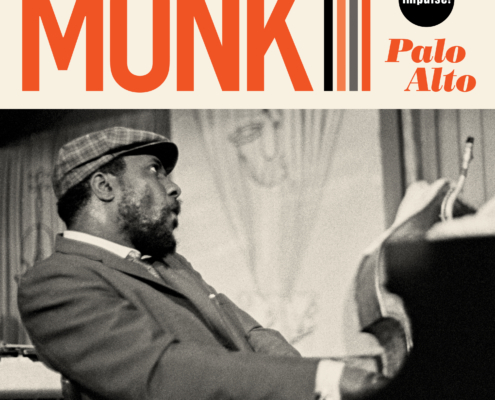

Thelonious Monk – Palo Alto

Das unveröffentlichte Konzert von 1968

- Ruby, My Dear(7:00)

- Well, You Needn’t(13:16)

- Don’t Blame Me(6:36)

- Blue Monk(14:02)

- Epistrophy(4:26)

- I Love You Sweetheart of All My Dreams(2:02)

Thelonious Monk – piano / Charlie Rouse – tenor saxophone

Larry Gales – bass / Ben Riley – drums

Recorded live at Palo Alto High School, Palo Alto, CA, October 27, 1968

Im Jahr 2018 erzählte Impulse! Records die Jazzgeschichte des Jahres mit John Coltranes Lost Album “Both Directions at Once”.

Im Jahr 2020 wird die Jazzgeschichte des Jahres die weltweite Erstveröffentlichung eines Live-Konzertes des legendären

Thelonious Monk sein – ein Konzert mit einer unglaublichen Hintergrundgeschichte…

Nach der Ermordung von Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. im Jahr 1968 nahmen die Rassenspannungen in den USA rasant zu. Auch Palo Alto, eine weitgehend weiße Universitätsstadt in Kalifornien, war gegen die Ereignisse jener Tage nicht immun. Danny Scher, ein aufstrebender Junior an der Palo Alto High School, hatte den Traum, Thelonious Monk dorthin zu bringen, um dort zu spielen, zur Einheit der Rassen in seiner Gemeinde beizutragen sowie Spenden für das Internationale Komitee seiner Schule zu sammeln.

Nachdem Scher sich auf kompliziertem Weg die Zusage von Monk gesichert hatte, am Sonntag den 27. Oktober an der Palo Alto High School aufzutreten, hatte er zunächst große Probleme, Tickets zu verkaufen, da ihm niemand glaubte, dass so ein Event zu dieser Zeit und an diesem Ort möglich wäre und der als exzentrisch bekannte Monk überhaupt auftauchen würde.

Nach vielen Drehungen und Wendungen, und erst als mehrere hundert Menschen auf dem Parkplatz der Schule auf die Ankunft von Monk warteten bevor sie Tickets kauften, fand das Konzert schließlich statt. Es wurde ein Triumph auf mehr Arten als Monk oder Scher es sich vorher hätten vorstellen können. Die wiederentdeckte Aufnahme dieses nicht nur musikalisch historischen Events erscheint jetzt weltweit erstmals auf LP, CD und digital.

Sowohl die LP als auch CD enthalten ein Booklet mit Erinnerungen von Veranstalter Danny Scher und Linernotes von Robin Kelly, sowie Faksimiles des damaligen Konzertposters und Konzertprogrammes.

INFO

For Thelonious Monk, 1968 was yet another banner year. Four years earlier, he had been featured in a cover story for Time Magazine that sparked an interest in and curiosity about his singular style and idiosyncratic music. Along with Miles Davis, who credited the pianist as a mentor, Monk was recording for major label Columbia Records. That 14-album stint began in 1962 and ended in 1968 with two LPs, Underground and Monk’s Blues. In the midst of those critical accolades during his Columbia years, Monk enjoyed a full schedule of touring dates in such jazz hotbeds as New York and San Francisco. During this time, Monk performed his brilliance as band leader and improvisor in the most unlikely setting: a small-stage 350-seat high school auditorium on a Sunday afternoon in the lily-white bedroom city of Palo Alto on the peninsula south of San Francisco (now part of Silicon Valley). That historic October 27, 1968 concert produced by teenager Danny Scher will be released for the first time by Impulse Records as PALO ALTO.

“That performance is the one of the best live recordings I’ve ever heard by Thelonious,” says T.S. Monk, son of the pianist/composer maestro, drummer and founder of the Thelonious Monk Institute. “I wasn’t even aware of my dad playing a high school gig, but he and the band were on it. When I first heard the tape, from the first measure, I knew my father was feeling really good.”

The vibrant 47-minute album spotlights Monk’s steady touring band (tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Larry Gales, drummer Ben Riley) and features his basic touring repertoire. Included in the mix is Monk’s lyrical love song “Ruby My Dear” (Rouse boldly blowing the melody with Monk comping in his unique oblique way then taking the lead with a dazzle); the dynamic and spirited “Well You Needn’t” taken for a 13-minute ride with solos by all members; the pianist’s captivating solo reading of “Don’t Blame Me” by Jimmy McHugh; an epic dance through “Blue Monk”; and a playful charge through ”Epistrophy.” The show ends with a truncated encore of Monk slowly striding through the 1925 Tin Pan Alley hit tune by Rudy Vallée, “I Love You (Sweetheart of All My Dreams)” and after a standing ovation saying his goodbye because they had to leave to make their San Francisco date that evening.

“It was a total pleasure,” says Scher, whose two idols in his youth were Monk and Duke Ellington (who he befriended in his teens). “There was nothing odd. I loved Monk, I loved his music, and I loved producing, It was great seeing Monk dancing around the stage and then coming back to the piano when it was the right time. There was zero drama.”

“This is one of the greatest examples of how important he was,” says T.S. “This is a milestone in Thelonious’ career. And the history behind it is a compelling American story at the height of the civil rights movement.”

At the time of the concert, the U.S. was in the midst of social turmoil accentuated by racial unrest. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., the powerful advocate for forging a back-white alliance, was assassinated. Two months later on June 5, the same fate befell Robert Kennedy, in the midst of a presidential campaign where he told a writer that blacks and poor whites have a common interest: “If we can reconcile these two hostile groups…you can really turn this country around.”

On October 16, less than two weeks before the Monk show, two black athletes at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City—track-and-field stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos—accepted their medals and raised their gloved fists in a black power/human rights salute during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It was a bold protest and highly controversial. It further fueled racial divisions.

At the time, Scher was a fledgling concert producer at his high school where he was passionate about jazz. He connected with jazz writers, radio DJs and helped put up posters for people presenting concerts. He was a drummer and threw himself into books on the history of jazz. Unbeknownst to his parents, when he was 15, he hitchhiked to the 10th anniversary of the Monterey Jazz Festival and hung out to meet artists. “The whole scene was very mixed racially,” he says. “I had never been around so many black people, and I had never been so welcomed. So I got autographs from Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald, and on the suggestion of Duke’s drummer Louie Bellson, I checked out Art Blakey and Elvin Jones. I wasn’t conscious of it at the time, but I was welcomed by the interracial community.”

In his junior year at Palo Alto high, Scher visited University of California Berkeley to help junior Cal student Darlene Chan who was launching the first Berkeley Jazz Festival. Scher volunteered to put up posters around his home town, and when he was old enough to have his driver’s license, to pick up artists such as Cannonball Adderley and Gil Evans from the airport. That inspired him to put on jazz concerts of his own at his high school. With the help of Chan and another key member of the jazz scene in Berkeley, Herb Wong, Scher started contacting artists and producing his first concert with Vince Guaraldi and Jon Hendricks and later presenting Cal Tjader. He convinced the school to permit him to wire the amphitheater so students could have their own radio shows on Radio X—his Thursday DJ slot was all about jazz, which resulted in record companies sending him LPs to play. Monk became his object of attention, and through Chan and Wong, he got the phone number of Monk’s manager, Jules Colomby. Since Monk was going to be playing an extended date at the Jazz Workshop club in San Francisco, they agreed on a Sunday afternoon for Monk to come to Palo Alto for a $500 fee. Scher’s high school principal sent the contract to Colomby. As the date came closer, Scher was concerned: the $2 tickets were not selling and there was no communication with the Monk camp. He put up posters all over town and got some sponsors from customers on his newspaper route. He then crossed the tracks and went into the predominantly black neighborhood of East Palo Alto to alert residents there that Monk was coming to town.

“The cops told me that was a dangerous thing for me to do, and there might be a racial issue if they came to Palo Alto high school,” Scher recalls. “But I knew that community knew all about Monk. I ran into a bunch of kids in an East Palo Alto parking lot and started to talk to them about the concert. No one ever challenged me or discouraged me or made fun of me. But they still didn’t believe me that I was inviting them to the show. So they came and waited in the school parking lot until Monk showed up before buying a ticket at the box office.”

Monk almost didn’t come. Two days before the show, Scher had to call the Jazz Workshop that didn’t allow minors. “I wanted to remind Thelonious about the show, but he had never gotten word about it,” Scher says. “And he said he didn’t have a car, so I said my older brother Les would pick them up. It all worked. Les drove up to the school with the bass sticking out the window, everyone saw that Monk had arrived, and they all got tickets. We sold out. Meanwhile, the school’s janitor had said he’d tune up the piano and tape the show. I held on to that tape for 52 years.”

“First, that concert is important to lovers of Monk,” T.S. says. “Danny had forgotten he had the tape. Some 15 or so years ago, he was cleaning out his attic, found the tape and contacted me. He wanted to put it out himself, but I said let’s talk about being partners.”

Second, T.S. says, is the consideration of the social ramifications at the time. “It reveals a lot about the power of music integrating the audience,” he says. “That nexus is so important. Here’s an African American genius responding to a 16-year old Jewish kid in a racist town. That’s what made Thelonious so important. People viewed Monk as a withdrawn artist. That’s how he was sold. Everyone loves a mad genius. He didn’t like to be portrayed that way, but he went along with the publicity campaign so that he could feed the family. But he was an extremely personal musician. The legend of him is very different than who he was.”

At Palo Alto, Monk played like he was freed from the record company wanting product and bringing together an audience that crossed the racial line. In that sense, this concert was a triumph for the time.

In the album liner notes, Scher writes, “Our predominantly white high school was trying to promote one of the most popular black acts. These issues never crossed my mind because I was, and still am, color blind to music. I always looked at music as a way to put issues on hold or up to a mirror, whether they be political or social…I never really thought of the political or racial ramifications other than Thelonious Monk is someone everyone should listen to, music is a solidifying event, and I wanted to produce it.”

Scher says that any semblance of racial division at the concert was not visible. There was truce between Palo Alto and East Palo Alto. “Race wasn’t an issue; it wasn’t a problem,” says Scher, whose forte for producing eventually led him to work as a key player in impresario Bill Graham’s production company BGP for more than two decades. “You can hear how pleased Thelonious was in playing that show. That was the beauty of it for one beautiful afternoon. People left the show and then went home to get back to battle.”

Radio-Kontakte

Media Promotion (Promotion Süd, West & Nord)

Rosita Falke

info@rosita-falke.de, Tel: 040 – 413 545 05

Musicforce

Anja Sziedat (Promotion Berlin / Ost)

anja.musicforce@gmail.com, Tel: 030 – 419 59 615, Mobil: 0177 – 611 5675

Impulse! Records / Universal Music

CD 00602507112851 / LP 00602507112844

Neuer VÖ: 18.09.2020